Donald Trump has set out a tentative timetable for sending Americans $2,000 payments funded by his tariff policy, telling reporters that the first so-called “dividend” cheques would not be ready until sometime in 2026, even as key details of the plan remain unclear and the underlying tariffs face legal and political challenges.

The former president first ignited expectations earlier in November when he used his social media platform to claim that the United States was earning so much money from tariffs that it could both pay down its debts and send a sizeable cash payment to most citizens. In a post that quickly circulated online, Trump wrote: “People that are against Tariffs are FOOLS! We are now the Richest, Most Respected Country In the World, With Almost No Inflation, and A Record Stock Market Price. 401k’s are Highest EVER. A dividend of at least $2000 a person (not including high income people!) will be paid to everyone.”

He presented the idea as a windfall generated by his aggressive use of import duties, arguing that the levies had transformed the US into a nation flush with cash and able to reward its people directly. Trump also tied the proposal to the national debt, saying tariff revenues were so strong that they would allow the government to start paying down what he described as “our ENORMOUS DEBT, $37 Trillion” while still funding the payments.

In the days that followed, the White House confirmed that the administration was actively working on a mechanism to deliver the promised $2,000 per person. Officials framed the plan as a way of redirecting money raised at the border back to households, emphasising that better-off Americans would be excluded. According to the administration’s own description, the proposed cheques would be targeted at low and middle-income families rather than the wealthiest earners.

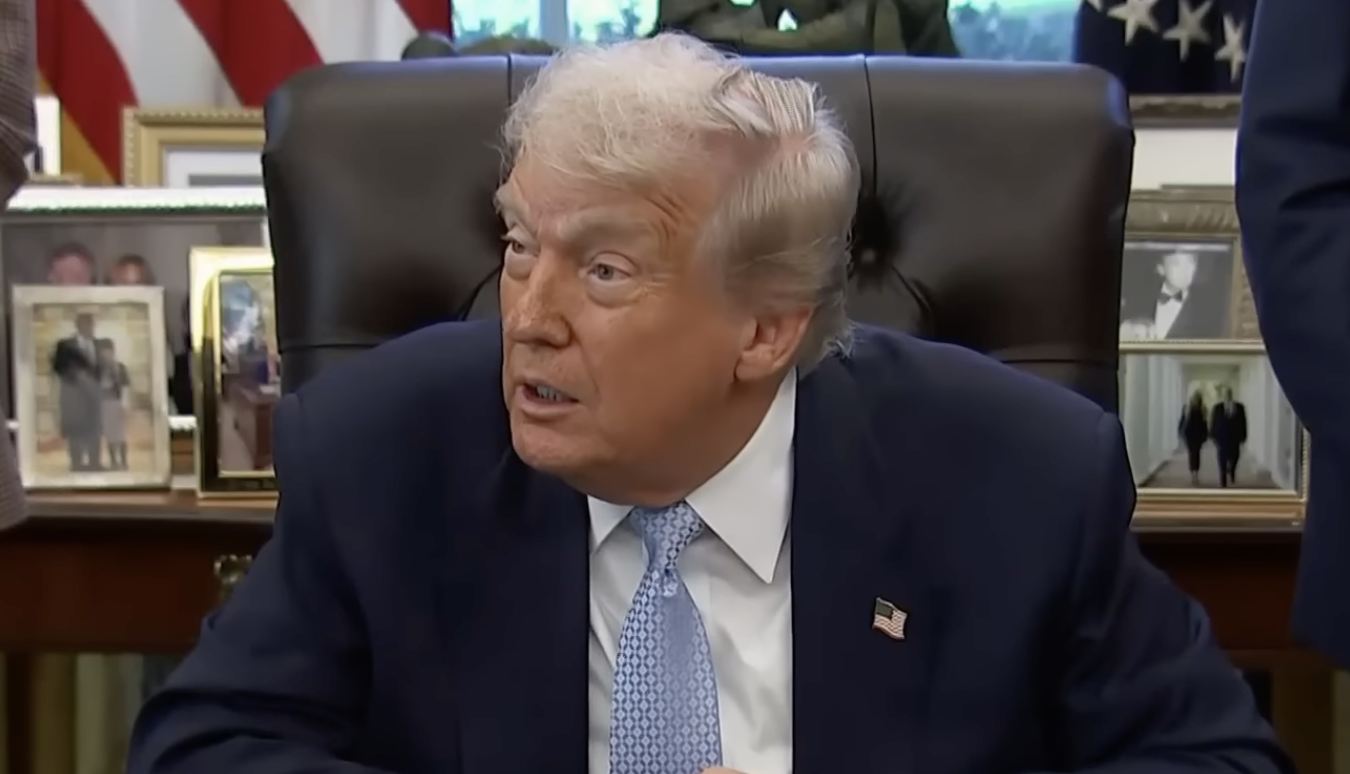

Trump has repeatedly insisted that the money will be real and will arrive, but has steadily pushed back the expected date. After initially suggesting in broad terms that Americans would see the benefit relatively soon, he has now said that the first cheques are unlikely to be sent before mid-2026. Speaking to reporters during recent engagements at the White House and aboard Air Force One, he said the government would be “issuing dividends later on” and added: “It will be next year… The tariffs allow us to give a dividend. We’re going to do a dividend and we’re also going to be reducing debt.”

In one exchange with journalists, Trump elaborated on the timing, saying that the payments would come “somewhere prior to, you know, probably in the middle of next year, a little bit later than that, of thousands of dollars for individuals of moderate income, middle income”. He linked the idea to what he described as “hundreds of millions of dollars in tariff money,” repeating his view that the US has taken in significant sums from duties imposed on foreign goods and that these revenues would underpin both the cheques and debt reduction.

Behind the confident rhetoric, however, the administration has yet to spell out how the tariff dividend would work in practice, who exactly would qualify or how often the payments would be made. The president’s Truth Social post, and subsequent public comments, referred to “at least $2000 a person” and excluded “high income people” but did not define the income threshold, how families with children would be treated or whether the cheques would be a one-off or a recurring benefit.

Senior economic officials have provided only partial answers. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has acknowledged that the administration is examining some form of $2,000 benefit, indicating in one television interview that officials were looking at limiting the payments to households earning around $100,000 a year or less. He also suggested that the “dividend” might not necessarily arrive as a physical cheque, floating the possibility that it could take the form of tax credits or other offsets instead. At the same time, Bessent has made clear that any such scheme would require legislation, saying during another appearance that “we need legislation for that” when asked if the plan would move ahead.

Commerce officials have signalled a similar approach, saying the aim is to focus the benefit on “people who need the money” while still presenting it as a direct return from tariff policy rather than a traditional welfare programme funded through general taxation. That framing reflects Trump’s longstanding political argument that tariffs are a tool for shifting the burden of financing government away from American citizens and onto foreign producers, even though mainstream economists point out that domestic importers are legally responsible for paying the duties and often pass the cost on to consumers.

The question of whether the numbers add up has become central to the debate surrounding the promised cheques. Public data indicate that Trump’s tariffs have indeed generated substantial revenue. The administration has said that the full slate of duties brought in roughly $195.9 billion through the end of August in the current fiscal year, while a subset of measures imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) has produced about $90 billion in receipts through late September.

However, independent budget analysts who have examined the proposal argue that tariff revenues on their own are not enough to fund $2,000 payments at the scale implied by Trump’s promise. One estimate from a leading tax policy group suggested that providing a $2,000 dividend to individuals below a $100,000 income cap would cost in the region of $300 billion, significantly more than the administration’s current take from tariffs. The same analysis warned that the plan could increase federal deficits by trillions of dollars over a decade if the payments were repeated, markedly outstripping projected tariff income over that period.

Legal uncertainty adds another layer of complexity. A large share of the revenue Trump wants to use is tied to tariffs imposed under IEEPA, a national security statute that does not explicitly mention customs duties. That strategy is now being tested in the courts, with the Supreme Court hearing arguments over whether the administration exceeded its authority in using emergency economic powers to levy broad tariffs. Several lower courts have already raised doubts, and justices have questioned aspects of the approach. If the top court ultimately rules against Trump on IEEPA, the government could be forced to unwind some of the tariffs and even refund money to importers, undermining the financial foundation for the promised cheques.

Trump himself has acknowledged that the legal fight could affect the policy’s future. When asked whether he would still move ahead with the dividend if the Supreme Court struck down his use of IEEPA tariffs, he responded: “Then I’d have to do something else,” without elaborating on what that alternative might be. Despite that caveat, he has continued to describe the tariff dividend as a central element of his economic agenda and has insisted that higher-income Americans will be left out of the benefit, though he has yet to define what counts as “high income”.

The rollout of the idea has also exposed divisions and uncertainty within Trump’s own economic team. Bessent has said in one interview that he had not discussed the dividend in detail with the president before the Truth Social post, and his public comments have alternated between defending the logic of targeting lower-income families and stressing that the plan is still under discussion. Other officials have emphasised the importance of using tariff revenues to reduce the national debt, a goal that could be at odds with large cash payments unless offsetting cuts or tax rises were introduced elsewhere in the budget.

Outside government, the proposal has drawn scrutiny from economists who note that earlier rounds of broad stimulus payments, such as those issued during the Covid-19 pandemic, cost hundreds of billions of dollars and were financed through increased federal borrowing. They also highlight that the economic impact of tariffs is more complex than the simple picture Trump has painted, with higher import costs feeding into consumer prices and potentially weighing on growth. Some analysts have questioned whether it is possible to use tariffs simultaneously to fund large-scale household cheques and meaningfully reduce the national debt, given the magnitude of both the proposed payments and existing borrowing.

For now, though, the political focus remains on the president’s own words and the expectations they have created. Trump has reiterated in several settings that Americans will receive “at least $2000 a person” from what he portrays as the spoils of his trade policy, presenting the dividend as both a reward for enduring higher prices and a symbol of national strength. He has linked the idea to broader themes in his rhetoric, from criticising opponents of tariffs as “FOOLS” to declaring that the United States has become the “Richest, Most Respected Country in the World” under his approach.

Whether those promises translate into money in people’s bank accounts will now depend on a sequence of hurdles that lie largely beyond a single social media post: congressional willingness to authorise such payments, the outcome of legal challenges to his use of emergency powers, the trajectory of tariff revenues and the broader state of the federal budget. Until those questions are resolved, the timeline Trump has now put forward, pointing to mid-2026 for the first cheques, remains a goal rather than a fixed date, and the $2,000 tariff dividend exists chiefly as a high-profile pledge at the centre of his economic message.