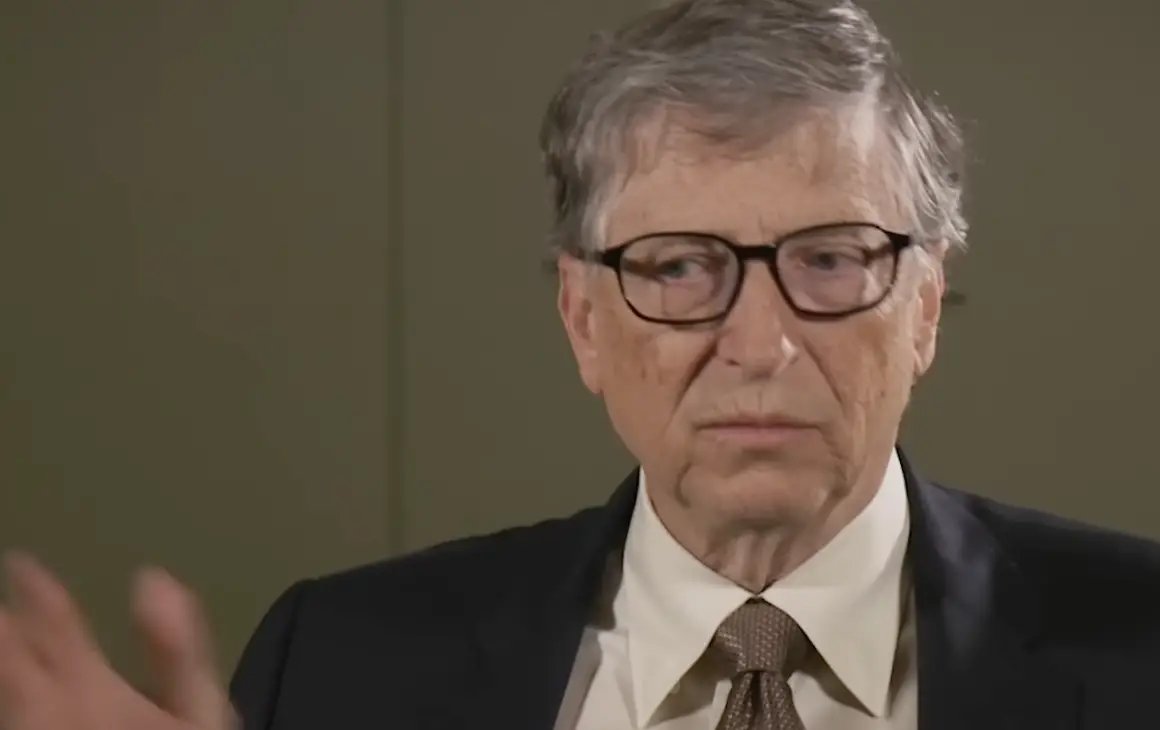

Bill Gates has warned that the world is on the brink of a historic reversal in child survival, with almost five million children expected to die before their fifth birthday this year as cuts to global health funding begin to erase decades of progress. New modelling for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s latest Goalkeepers report projects that deaths among under-fives will rise from 4.6 million last year to about 4.8 million in 2025, the first increase this century in a statistic that had been steadily falling since 2000.

Gates has described the shift as a “significant reversal in child deaths” and a stark warning about what happens when governments pull back from long-standing commitments to global health. Speaking about the projections, he has repeatedly stressed that the grim numbers do not reflect a failure of science or a lack of effective tools but a collapse in the political will to pay for them. In an article for his foundation earlier this year he noted that the world had already achieved something “stunning,” cutting annual child deaths from more than 10 million in 2000 to fewer than 5 million today through vaccines, basic healthcare and better nutrition. The new forecast shows that this trajectory is now in danger of running in reverse.

The Goalkeepers analysis, carried out with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, links the uptick in deaths to a sharp fall in development assistance for health. According to figures cited by the foundation, global health aid is estimated to have dropped by almost 27 percent in 2025 compared with last year, after a series of budget decisions by major donors. Reuters reported that aid reductions began in the United States and were then followed by other large contributors, including the United Kingdom and Germany, at a time when many lower income countries are already struggling with rising debts and fragile health systems.

The practical effect of those cuts, Gates argues, is measured in children who do not receive vaccines, medicines or basic primary care. He has written that “there’s something especially devastating about a child dying of a disease we know how to prevent,” stressing that many of the projected deaths are from illnesses such as malaria, diarrhoeal disease and respiratory infections that can be treated or avoided altogether with proven interventions.The new figures suggest that if current funding reductions become permanent, as many as 16 million additional children could die between now and 2045 compared with a scenario in which support had been maintained.

Gates has sought to frame the situation as a choice rather than an inevitability. In interviews and opinion pieces he has emphasised that “it does not have to be like this,” arguing that the world still has both the tools and the financial capacity to drive child mortality far lower if governments maintain relatively modest commitments. He points out that rich countries spend only a small fraction of their budgets on global health and development and contends that continuing to allocate roughly 1 percent of public spending to those areas can save millions of lives while also strengthening global defences against future pandemics.

The warning comes at a politically sensitive moment, with several donor governments facing domestic pressures to rein in spending abroad. The United States has restructured elements of its aid apparatus, and other countries have scaled back previous pledges as they deal with slower economic growth and competing priorities at home. Gates has said that private philanthropy, including his own foundation’s resources, cannot fully replace those public flows. The Gates Foundation has committed more than 100 billion dollars over its first quarter century and plans to double its giving over the next 20 years, but he has repeatedly underlined that such efforts are intended to complement, not substitute for, government action.

In September he used an appearance on CBS News to urge United States lawmakers to protect global health funding as they negotiate budgets. He told “CBS Mornings” that for 25 years the world had seen “miraculous” progress as child deaths fell from over 10 million to under 5 million per year and said it would be a profound mistake to allow 2025 to become “the first year that more children die than the year before.” Around the same time he announced a pledge of 912 million dollars over three years to support programmes targeting HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, describing the moment as a crossroads that would show whether countries were prepared to continue playing a role in saving lives beyond their borders.

The new Goalkeepers projections build on that message by quantifying what is at stake. The modelling suggests that without renewed investment, deaths among under-fives will climb to around 4.8 million this year. Gates has stressed that the figure is an estimate rather than a precise tally, but it is used by the foundation to highlight the underlying trend and the risk that hard-won gains could be lost. The headline number of five million deaths reflects the scale of the problem, rounding the projection to signal how many young lives are in jeopardy.

Behind those statistics are familiar global health priorities that have dominated the foundation’s work since it was created in 2000. Vaccination campaigns against diseases such as measles, polio and pneumococcal infections have been credited with saving millions of lives, particularly in low and middle income countries. Programmes supported by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and by the vaccine alliance Gavi rely heavily on donor funding to purchase medicines, deploy community health workers and strengthen clinics. Gates argues that when budgets for those institutions are cut or delayed, the consequences quickly show up in missed vaccinations, stockouts of drugs and weaker disease surveillance, all of which increase the risk of preventable deaths in early childhood.

The rise in child mortality also intersects with broader pressures on health systems. Many countries are still dealing with the aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, including disrupted routine care and backlogs in immunisation that left millions of children unprotected. Others face conflict, climate-driven disasters and economic crises that push families into deeper poverty and make it harder to access care. Gates has said that shrinking aid budgets in this context amount to “pulling back just when the need is greatest,” warning that the world risks sending a signal that progress for the poorest is no longer a priority.

At the same time he has tried to maintain a note of conditional optimism, arguing that technological advances give governments a powerful opportunity to reverse the negative trend if they choose to use them. In his recent essay on global health he highlighted new tools such as AI-enabled systems for detecting outbreaks, improved diagnostic tests and innovative mosquito control strategies that can reduce malaria transmission. He has argued that if countries sustain or increase their current levels of health spending and help scale up those innovations, the world could cut child deaths in half again over the next two decades, echoing the progress made since the turn of the century.

Gates’s interventions are partly aimed at domestic audiences in donor countries and partly at leaders in low and middle income nations who make decisions about how to allocate limited resources. In his CBS interview he framed the issue in moral terms, asking whether it is possible to pursue an “America first” agenda while still keeping “the charity for that 1 percent” of the federal budget devoted to foreign aid. In other forums he has emphasised the mutual benefits of investing in global health, arguing that stronger disease detection and response in poorer countries can help prevent outbreaks from reaching richer ones and that healthier populations are more likely to become stable trading partners over time.

The warning that nearly five million children could die before their fifth birthday this year is therefore both a description of current trends and a rhetorical device intended to galvanise action. The foundation’s modelling shows what is likely to happen if existing commitments continue to erode, but it also maps out scenarios in which deaths continue to fall. Gates is urging governments to choose the latter path by restoring and protecting health budgets, supporting multilateral institutions and ensuring that innovations such as new vaccines and diagnostics reach the children who need them most.

For families in the hardest hit regions, the debate over line items in rich countries’ budgets translates into the most personal of outcomes. The difference between a fully funded vaccination campaign and one that falls short can be measured in the number of children who live long enough to attend school, grow into adulthood and contribute to their communities. Gates has warned that the current trajectory risks creating what he has described as a generation that had access to unprecedented scientific advances “but could not get the funding together to ensure it saved lives.”

The latest projections show that without swift action, the world is heading into a period in which deaths among young children begin to rise again after a quarter century of steady decline. For Gates the message is blunt. The tools to prevent those deaths exist. Whether they are used at the necessary scale depends on decisions being taken now in parliaments and finance ministries far from the villages and clinics where the impact will be felt.