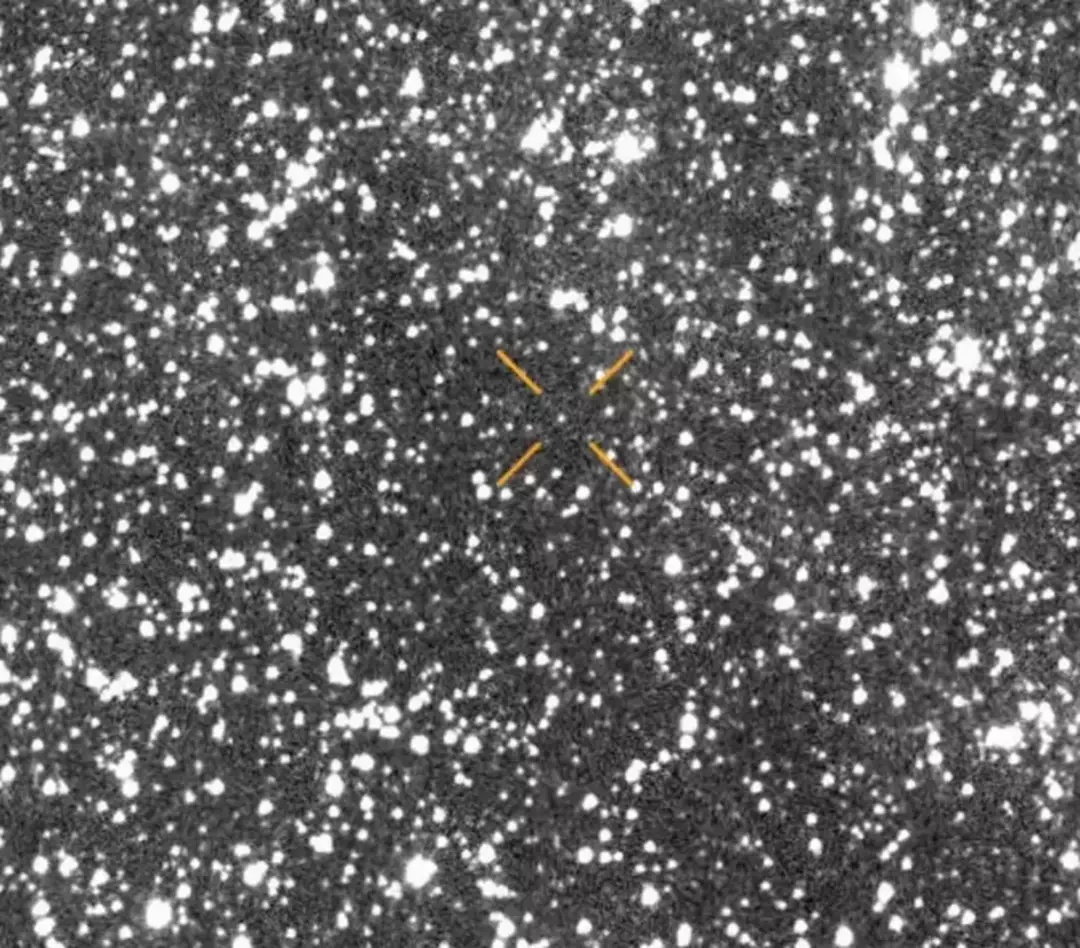

Astronomers around the world were watching closely as an interstellar visitor known as 3I/ATLAS approached what scientists have described as its closest point to Earth, an encounter that has prompted intense observation, fresh analysis of its trajectory and renewed online speculation about what, exactly, the object might be.

3I/ATLAS is the third confirmed object observed passing through the Solar System on a path that indicates it originated beyond it. NASA has said the object poses no danger to Earth, stressing that even at its closest it remains at a vast distance, with the agency putting the closest approach at roughly 270 million kilometres, or about 170 million miles.

Despite that, the approach has attracted outsized public interest, fuelled in part by social media commentary and by the object’s unusual observational circumstances. NASA notes that 3I/ATLAS will reach perihelion, its closest point to the Sun, in late October 2025, but that this will occur when the object is on the far side of the Sun from Earth, making it difficult or impossible to observe with many Earth-based telescopes at the most critical phase of its activity.

The “new strange behaviour” highlighted in online discussions has largely centred on evidence that the object is not moving like an inert rock. Instead, it appears to be experiencing small but measurable non-gravitational accelerations, subtle changes in its trajectory that are common in comets and are typically driven by jets of gas and dust released as sunlight heats the surface. A recent analysis submitted to Research Notes of the AAS reported “significant non-gravitational accelerations (NGAs) in the 3I/ATLAS trajectory,” using a combination of ground-based observations and additional measurements from interplanetary spacecraft that observed the object from vantage points unavailable on Earth.

That work, led by T. Marshall Eubanks and colleagues, said the inclusion of six observations from two spacecraft reduced uncertainties in the non-gravitational acceleration parameters compared with solutions relying only on terrestrial data, and it modelled the acceleration in a way consistent with outgassing, particularly from carbon dioxide. The paper notes that “outgassing thrust from sublimating CO, CO2, and H2O can cause noticeable cometary NGAs,” and cites previous work indicating the coma of 3I/ATLAS is CO2-dominated.

Such measurements matter because they allow researchers to infer physical properties that are otherwise difficult to pin down, including rough mass and size estimates. The same analysis offered a “rough mass estimate” and a constraint on a possible nucleus radius under certain assumptions about composition. While those estimates remain model-dependent and subject to revision, they reinforce a central point in mainstream interpretations: observed “behaviour” in the object’s motion can be explained within normal comet physics, rather than requiring extraordinary explanations.

Even so, the object’s interstellar origin and the observational gap around perihelion have helped drive a parallel narrative online, including the claim circulating in some corners that it might be an “alien object” and, in more extreme versions, potentially hostile. That language has tended to spread through commentary rather than through official scientific classification. In formal terms, the object is treated as a comet-like body, and NASA has framed it as a scientific opportunity rather than a threat. “There is no threat to Earth posed by asteroid 2024 YR4,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a separate context on planetary defence messaging, reflecting the agency’s broader approach to clarifying risk when public attention spikes around near-Earth objects.

One reason 3I/ATLAS has become a magnet for speculation is that it joins a very short list of confirmed interstellar objects, following 1I/‘Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. With only three examples, scientists are still building a statistical and physical picture of what kinds of bodies are likely to arrive from other star systems, how often they appear, and how their compositions compare with comets and asteroids formed closer to home. NASA’s fact sheet for 3I/ATLAS highlights the simple but powerful point that it is “the third known interstellar object discovered passing through the solar system,” underscoring why researchers want to extract as much information as possible from a brief fly-through.

Because perihelion will be poorly placed for Earth-based observing, researchers have also looked to spacecraft already operating elsewhere in the Solar System to fill the gap. An arXiv paper examining potential observing opportunities argued that 3I/ATLAS will pass “relatively close to a number of already launched interplanetary spacecraft,” and mapped potential windows for data collection from multiple missions and platforms, including spacecraft near Mars and those on heliocentric trajectories.

That planning is not just about getting pictures. Different observing geometries can help constrain brightness changes, dust production, gas composition and the structure of the coma and tail. If outgassing is indeed the driver of the object’s non-gravitational acceleration, measurements taken from different locations could improve estimates of how strong the jets are, when peak outgassing occurs, and how the object’s rotation influences its activity. The Research Notes analysis included a time offset parameter indicating acceleration that peaks before perihelion, a pattern that can occur in comets when thermal effects and seasonal illumination change how and where gas vents from the nucleus.

The story has also highlighted the tension between scientific uncertainty and the internet’s appetite for definitive answers. While scientists can say with confidence that 3I/ATLAS is not on a collision course with Earth, and that its distance at closest approach remains enormous, they are still working to refine details about its size, density, exact composition and the mechanisms behind its observed activity. NASA’s public-facing material has been blunt about the lack of danger while also emphasising the object’s value as a natural experiment: an opportunity to study material formed around another star, now briefly accessible to human instruments.

As the closest-approach window passes, attention will shift toward what observations can still be gathered as the object continues its journey, and toward how researchers interpret the data already collected. The evidence of non-gravitational acceleration, strengthened by spacecraft-based measurements, is likely to remain central to that discussion, because it is both a clue to the object’s physical nature and a key to predicting its future path with higher precision.

For now, the most defensible description of 3I/ATLAS is also the least sensational: a rare interstellar comet-like body whose motion shows signs consistent with outgassing, passing far from Earth and offering scientists a limited-time chance to probe the chemistry and dynamics of a visitor from another part of the galaxy. The more dramatic language circulating online may persist, but the trajectory calculations and the physics-based explanations emerging in the literature point to a familiar kind of “strange behaviour” for astronomers who study comets: the gentle push of sunlight turning ice into gas, and gas into a tiny but measurable thrust.