In a laboratory at a Dutch university hospital, a small group of researchers set out to answer a question that had lingered in textbooks, sketches and speculation for centuries: what, precisely, happens anatomically during sexual intercourse and female arousal.

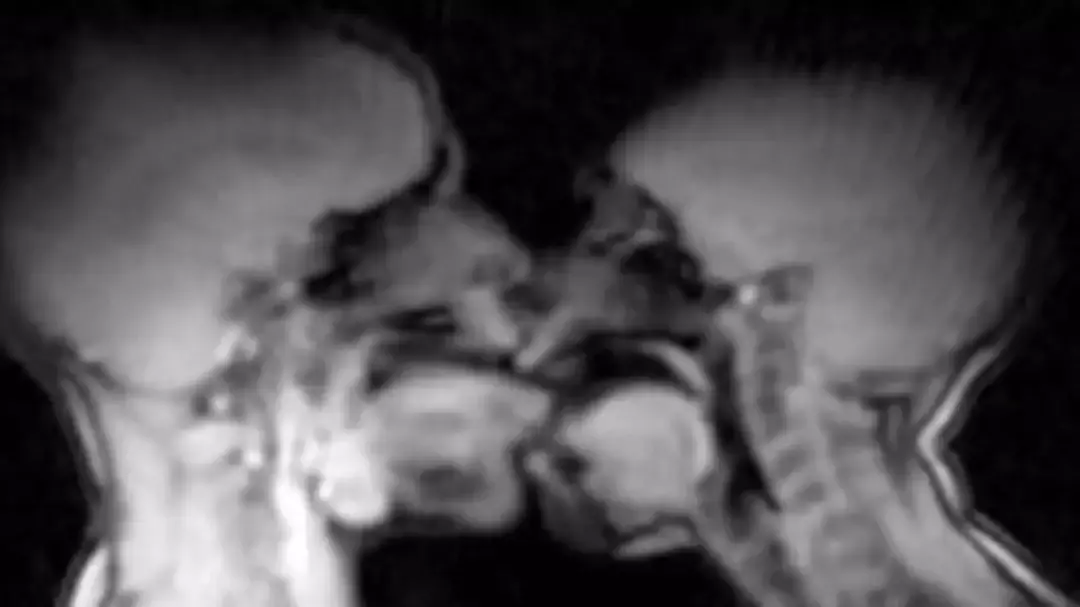

Their answer, recorded not with illustration or assumption but with magnetic resonance imaging, produced a set of findings that have repeatedly resurfaced in public conversation, decades after the work was first published. The study, which involved real-time MRI scans of volunteers during arousal and intercourse, concluded that capturing usable images of coitus was feasible and that some long-held ideas about the mechanics of sex were wrong.

The research, published in The BMJ, was explicitly framed as an attempt to separate fact from inherited theory. Its authors wrote that the “scientific study of the interaction of human genitals during coitus and after ejaculation with and without female orgasm has always been difficult and controversial with ethical, technical and social problems”, quoting earlier work on the subject. They added: “We experienced this personally. It took years, a lobby, undesired publicity, and a godsend (two tablets of sildenafil 25 mg) to obtain our images.”

The project produced 13 experiments involving eight couples and three single women. MRI was used to study female sexual response and the male and female genitals during intercourse. In the most widely cited anatomical finding, the images suggested that during intercourse in the missionary position the penis was neither straight nor “S” shaped, but instead took on what the researchers described as a boomerang shape, with about one third of its length consisting of the root of the penis inside the body.

Alongside the imagery of intercourse, the study reported observations during female sexual arousal without intercourse. The researchers said the uterus was raised and the anterior vaginal wall lengthened, while the uterus itself did not increase in size during sexual arousal. They presented the work as a contribution to anatomical understanding, rather than a clinical breakthrough, concluding that taking magnetic resonance images during coitus “is feasible and contributes to understanding of anatomy.”

The paper also anchored its motivation in the long history of anatomical conjecture. In its introduction, it referenced Renaissance-era efforts to depict sexual anatomy, including a line attributed to Leonardo da Vinci written above a drawing of intercourse: “I expose to men the origin of their first, and perhaps second, reason for existing.” The authors noted that such sketches represented the best attempts of their time, but were rooted in theories that could not easily be tested.

Even with modern imaging, the study described significant practical challenges. The researchers wrote that male participants had more difficulty maintaining an erection in the scanner environment than the women had achieving a sexual response. They reported that all the women had a “complete sexual response”, but characterised the orgasms described by participants as “superficial.” Only the first couple, the authors said, was able to perform coitus adequately without sildenafil in the earliest experiments. The paper offered a possible explanation, suggesting that this couple’s unusual familiarity with performing under pressure may have helped.

The study also documented what it could not show. The authors wrote that it was not possible on the MRI images to distinguish clearly between the vaginal wall, the urethra and the clitoris. They added that the images did not show widening of the vaginal canal, structures suggesting a Gräfenberg spot, or a separate reservoir of fluid indicating female ejaculation. Those limitations have continued to be cited in later discussion of what imaging can, and cannot, resolve about sexual response.

Over time, the research became known not only for its scientific content but for its cultural afterlife. A later feature reflecting on the paper’s history described how the team dealt with “reluctance by hospital officials”, “sniffing press hounds” and problems with sexual performance, but still achieved images that captured intercourse in progress. That account also summarised the study’s main findings as overturning assumptions about penile shape and reporting that the uterus does not enlarge with arousal.

The same feature reported that the paper went on to win an Ig Nobel prize for medicine, an award that highlights research that first makes people laugh and then think. It quoted Tony Delamothe, a former BMJ editor, describing the appeal of the study as partly rooted in the novelty of the images, writing that it contained “a striking image using a new technology, and everyone agreed that readers might be interested to see it.”

While the research itself was narrow in scope, focusing on a small number of experiments and a specific imaging setup, it has been repeatedly invoked when viral headlines claim it “changed” a belief that had persisted for hundreds of years. In practice, the belief being challenged is not a single written doctrine but a generalised assumption, reinforced through sketches and static models, about what the penis and surrounding anatomy look like during penetration. The authors argued that MRI allowed those assumptions to be tested directly.

The work also sits within a broader scientific effort to understand sexual function with objective tools, a topic that has often been limited by ethics, privacy and practical feasibility. The researchers themselves cited those barriers, emphasising that the interaction of genitals during coitus had long been “difficult and controversial” to study, and presenting their images as proof that at least some anatomical questions could be addressed with careful design and participant consent.

Decades after the scans were performed, the study remains one of the most recognisable examples of medical imaging applied to an intensely private human activity. Its findings continue to be circulated online, frequently accompanied by the same core details: the feasibility of imaging sex in real time, the boomerang-shaped configuration observed during missionary intercourse, and the reported changes in uterine position during arousal without evidence that the uterus increases in size.